- Home

- Joseph N. Love

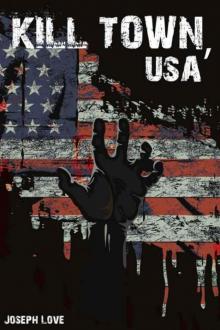

Kill Town, USA

Kill Town, USA Read online

Kill Town, USA

by Joseph Love

Kill Town, USA (Manuscript) Copyright © 2010-12 by Joseph Love

Kill Town, USA (Cover Art) Copyright © 2012 by Jeff Stiver

All rights reserved by contributors.

This eBook is not protected by DRM (Digital Rights Management). However, selling or profiting from the distribution or reproduction of its content is still illegal. Share it, don’t rip it off.

This novella was made available to the public through funds raised on Kickstarter.com. The author would like to thank the following backers for their significant contributions:

Joey Barnard

Bradtv

Kevin Cumesty

Kade Goodspeed

Ben Handy

Jodi Heavner

George O. (Pete) Love

Allen Mooney

Gail Mooney

Cindy DeGeorge Nance

Adam Rains

Alyssa Riedy

Ashe Smith

JoAnn Smith

Sissy Story

For Anna and Willa

I KILLED MY FIRST BEAR WHEN I WAS EIGHT, killed maybe half the population in Quinn Valley by the time I was sixteen. I’ve trapped snapping turtles with little more than broken brooms and shoeboxes. I’ve handled snakes, raccoons, and an otter I found in the roots of a swamp oak once. Not much I’d say I was afraid of. But I never had such a fear as when I saw that half-dead bear in North Carolina.

I worked accounting for Major Meat, Inc., supplier of beef, poultry, pork, and all sorts of hybrids, byproducts, and synthetic meats to forty percent of all the restaurants, groceries, and fast food joints in the country.

I didn’t do payroll. I did beef. Pitted slaughterhouses against each other to drive down costs. Forged counter-offers to drive up prices. I’m the reason your crunchy taco costs twenty-nine cents, and why you pay twenty bucks for a New York Strip. You know what New York Strip costs? Twenty-nine cents. Taco meat? Free. Scraps from the slaughterhouse floor.

That said, you couldn’t catch me saying a word against Taco Toro’s tacos. A little chili powder, sour cream, and shredded lettuce and I still ate the things.

There are some people who would kill to get the information I handled. Or write a big check. Nick Tolchik was the man with the big check and a thousand questions. A year back I got an email from Tolchik asking to meet me and talk about meat. He was some sort of bestselling muckraker, but I’d never heard of him. He emailed me weekly. Then, daily. He called me on my direct line after only a month. I gave in when he said he was in town and could meet me on my lunch break. He never mentioned anything about money.

We met at The Big Ass Bar, where we sat dwarfed by the big ass bar made of hickory slabs. I showed him my work folder: the food bill for the largest mass-consumer in the world. Technically, that information was public knowledge. He gawked at the red scribbles, green plus signs, and the huge margins of blue ink detailing marketing minutiae. The thing that got him was the table for canned taco meat. By replacing half an ounce of meat with shredded tendons in every ten-ounce can, Major Meat got a six-figure bump in profits every month. Tolchik was so excited to read it he wrung his napkin through his waxy fingers until I thought they’d bleed. He wrote me a check and slid it under my nose. I looked at him like he’d shit all over the big ass bar.

The next week I had a voicemail played aloud in front of my supervisor. Tolchik called the wrong number. He left a message on the wrong phone. I was given a month of unpaid suspension. I didn’t argue. That’s what you do when you work for someone, you don’t argue. You don’t complain. You take their money twice a month and you keep your mouth shut. But a month is a long time. I cashed Tolchik’s check and sent him an email telling him about the suspension and asking about the book. He said my folder gave his book a brand new angle. Gave it the angle. Tolchik’s agent got him out of his first contract, put the book up in a last minute auction, and had the publishers scrambling to sign him. The book was going to destroy Major Meat, Inc.

When my suspension was up, I stayed with Major Meat almost another year. They took away my office and gave me catch-up work to do. Payroll. I expected to get canned any day. When the economy tanked, I knew it wouldn’t be long. Then, Tolchik’s book came out in September. Major Meat stock dropped every day. On October 1st, a security guard met me in the lobby with a small banker’s box full of my things. On top was a hardback edition of Tolchik’s book, Major Murder: How Big Meat is Killing America.

Good thing, though. On October 15th, Major Meat recalled two thousand tons of toxic beef. A week later, it was three thousand tons of pork. Nearly two million patrons of Taco Toro, Big Wiggly Burgers, and Venni Vetti Beefy were placed in intensive care. Millions of pounds of meat were recalled weekly. By the end of the month, Major Meat was bankrupt. About half the patrons died from the beef. The rest went comatose.

And I went on vacation.

Even though I grew up in Quinn Valley, Georgia, just a few miles from the Appalachian Trail, I never spent much time hiking. I loved hunting, fishing, and camping in the valley. I grew up hearing how the Trail was for hippies and how they were turning Quinn Valley into a tourist trap. Hikers clogged up parking lots while they stayed on the trail for days at a time. They came like birds in the spring and summer, and like birds they got out of there by the first frost.

For years, Dad could only find seasonal work. He hated the onset of winter. Bear and tourist seasons were over and his arthritis flared up pretty bad. He tried to make money by selling firewood. In a place like Quinn Valley, people don’t pay for firewood. Winters were the worst. By the time the first snowfall came, you could hardly get Dad to eat anything.

Worse, there was no way he’d leave the house to work. I went to work when I was old enough and I stayed away from the Trail. But the Appalachian Trail is an inspiring thing. Two thousand miles of the hardest terrain, isolated from simple conveniences. When Major Meat laid me off, I was happy to be out of work and to have free time. It meant I could finally hike the Trail. I was happy to see the winter. Happy to wake to snow and frost, to shit in the woods, to go without. To carry a knife and rations and sleep on hard ground.

I’ve been face to face with black bears, and black bears don’t bother me. But what I saw a month out on the trail was just the shell of a black bear. Inside that shell was something dark, depraved.

I met a lot of hikers once I started the Trail, and I didn’t believe their stories about recent bear sightings. After all, you might see a bear in winter if it had been a hard summer or fall. I thanked all the folks with long, dirty hair and bead necklaces and rolled my eyes as they walked away. A bear in winter is a weak, unthreatening thing.

Still, I slept naked to avoid casting the smell of food into the forest. In the mornings, I basked in the frost and drank my coffee before I dressed again. I only dressed when I was ready to carry on. That’s something you learn early. Always enjoy the stillness, the rest, even in winter.

But the bear came. At three-thirty one morning, sound asleep, I woke to the tortured silence of night. Bears whisper when they walk. Their huge paws gently shake the ground. I felt the shaking of the frozen dirt. I heard the screaming quiet of his stealthy gait.

I slept naked, but not without my hunting knife. The fourteen-inch Gerber All-Or-Nothing. With only the knife, I slipped out of my sleep sack and stood in the opening of the shelter. The frost and moon made the ground shine. That’s when I saw the bear. Its black body trudged toward the fire pit from the right side of the shelter. It turned to me, eyes silver like the frost. We were alien to each other.

In the silence, there was a sound like running water. Fast and steady. In the faint moonlight, I saw something wet covering its face. I hate to say the thi

ng was even a bear. It was beyond animal.

The bear stood on its hind legs and bellowed a wet, raspy cry. It fell to all fours and lunged at me through the frost and brush, its paws pounding the dirt. Numb from cold, I scarcely dodged the bear before tripping through a pile of kindling. The bear tore through my sleep sack and plowed headlong into the wall.

Confused and angry, the bear swiped through the broken timber and turned to me, tongue dribbling. I gripped the Gerber’s neoprene handle and braced myself against the stirring wind. It launched at me in an awkward, galloping leap. I sidestepped, but its paw landed on my hip and I grabbed the fur for balance. The bear was a ball of cold and matted steel wool. We fell together. The icy mud burned my skin. I thrashed underneath, wielded the long blade, and sank the knife deep into the dark, frozen fur. The handle made a sucking noise at the wound. The bear’s blood ran cold and black down my arm.

His knee crushed my scrotum. I was lost in the pain and the darkness of his fur.

I raised the knife to its neck and hacked like a mad, desperate bastard. Its body went limp on top of me. The furry ice cube sank and I thought I might die underneath it, naked and cold and victorious. Its knee released my genitals. I squeezed out and retrieved the hunting knife. The bear’s blood clung like jam to the blade.

In the dark, I limped to my backpack hanging from the steel cables and lowered it to the ground. I didn’t notice until I tried to remove the pack from the cable that my hands were numb. I was shaking and every bit of my skin could have been frostbit. I knocked off the layer of crusted mud and put on my long underwear and thermal vest. Though I hadn’t slept long, I left the campsite for the next trailhead ten miles away. Even when I was warm and far away from that place, I shook nervously. I looked over my shoulder every fifty yards. I could see nothing in the dark, but I looked anyway. I kept watch religiously.

I’ll tell you again. There wasn’t much I was afraid of. I was thirty, seasoned and all-knowing. After that night, I was just thirty. I had been afraid of that bear.

I was a long way from home. Nearly four-hundred miles from the trailhead in Quinn Valley. Going home wasn’t an option. I decided to take a break in Hot Springs and stay off the Trail. Maybe the winter would pick up, snow a few inches, and drive the bears back to their dens.

By daybreak, I’d made it to Max Patch Mountain, a bald peak ten miles from Hot Springs. Up on the hill were sheets of ice scattered across the dead grass. There was no sun. Just a thick wad of clouds in blue and purple and yellow.

On top of Max Patch the wind was harsh. It tore through all my layers. The sky was much darker when I made the summit. It looked like snow forever.

Ditching my pack, I knelt and opened my emergency rations: two king-sized candy bars and a flask of high-proof whiskey. Halfway through the first candy bar, I unsheathed the hunting knife to clean it in the grass. The blood was almost black, thick as honey, and it stuck to the knife like no blood I’d seen. I stabbed the earth several times and wiped the mud on a tuft of grass. The blood still clung to the blade in streaks, shiny and wet.

“That’s one way to go hunting,” a hoarse voice giggled in my ear.

I spun and thrust out the knife. A white-haired hippie took a step back and put up his hands.

“It’s only a joke, take it easy.”

His dog huffed.

I lowered the knife.

“Want a hot drink?”

I shook my head and showed him the flask. I took a sip and offered him the flask.

He took the flask and put it to his lips, wincing as he swallowed.

I squatted, eye level with his dog, a black and white sporting breed. A handsome dog. It sniffed me out of obligation. Lowering its head, it lapped eagerly at the knife blade. I shoved its snout away. It growled. The hippie took another swig. The dog went back for the knife.

“She doesn’t like you pushing on her.”

“Well, no shit. I don’t think she ought to lick this knife.”

“It won’t hurt her.”

“I don’t know.”

“What’d you have on the end of that thing?”

“A bear.”

He curled his lip. “You don’t have anything better to do than go after a bear? You know, their numbers are dwindling because of people like you.”

“It attacked me.”

“They don’t do that unless provoked.”

I stood, sheathed the knife, and donned my pack. “Thanks for the advice.”

I looked across the valley at the clouds on the tops of the surrounding mountains. I gave the hippie another glance. He’d turned away and thrown a stick for the dog. It smelled like cigarettes all of a sudden. I noticed a pack of Pall Malls poking out of his breast pocket. A lit cigarette dangled from his lip. I intended to leave the hippie at the top of the mountain, but as I went to descend the hill I saw nothing but thick fog on all sides.

“Isn’t there supposed to be a parking lot down here?”

“Better be. That’s where I parked. It’s down this way,” he pointed opposite where I stood and struck off in a fast stride down the hillside.

“Name’s Tom,” he called over his shoulder.

“Jack,” I answered.

He stopped and took my hand with a firm grip. He gave it a single, unceremonious snap. “That’s it? Just Jack?”

“Excuse me?”

“Not Jack Lionheart or Bramblefoot Jack or Skidrow Jackie or something?”

“What are you talking about?” I stepped around him and continued down the hill.

“Most hikers give themselves a Trail name. Stupid if you ask me. Buncha hippie crap. I bet you’re running low on food. You set up any food drops?”

I laughed.

“Of course not. You’re the kind of guy who wants to go all on his own. No help. I bet you have a credit card.”

I laughed again.

“A wad of cash, that’s what you carry! And you keep it tucked in your clothes. And you always carry the knife.”

“You’re getting the idea.”

“Well, you’re going the wrong way, aren’t you?’

“No. I plan to make it to Hot Springs and rest. A week. Two weeks.”

Tom whistled just to whistle. “I’m not exactly a shit-in-the-woods kind of person. I’ll come up here with Carla once a week, but I’m not much into camping.”

“Is Carla your wife?”

He frowned and pointed to the handsome dog rolling in the snow. “Carla. I live pretty close to Hot Springs. You’re more than welcome to a shower and some coffee. I can drive you into Hot Springs, too. Maybe buy you some out-of-season oysters at Rock Bottom.”

His truck was a rusty, canary yellow International Harvester. Carla excitedly leapt up on the opened tailgate and climbed into the passenger seat. She showed her teeth at me through the window. Tom yelled at her and she sheepishly relinquished the seat to me. The door made a shotgun bang as I opened it.

Tom fired up the truck and turned a dial on a small space heater bolted between the seats. Wadded wrappers from Taco Toro decorated the floorboard.

“The heater takes a few minutes to warm up.”

The ball of wires taped to the back of the heater sizzled and smoked. Then, the smell and the smoke disappeared as Tom gunned the gas.

“Couple things, Jack.”

I opened the flask and took a long drink.

“You’re dumb and you’re lucky and you’re dumb.”

“Okay.” I was content to keep it at that. After a month of hiking, I’d been called all sorts of names for hiking in winter. I’d also been told about a hundred maladies, including: frostbite, snakebite, bearbite, batbite, rabies, poison gas from rat feces, deer-rape, bone-rattle, and twisty ankle syndrome. I wasn’t starved for the ignorance of others.

“You ought not accept a ride from the first person you meet.”

I shrugged.

“But you’re lucky because I’m not the kind of person you shouldn’t take a ride from.”

“Hm.”

“And you’re brave—or dumb—to fight off a bear. I guess it doesn’t matter who gives you a ride, does it?”

I looked at myself in the side mirror. With a full beard and greasy, matted hair, I didn’t look like someone who should be afraid of taking rides from strangers.

The heat from the buzzing orange coils filled the drafty, moldy cab. My window turned foggy and green. The condensation dripped down to the cracked rubber seal on the door. Carla huffed in the back seat.

I didn’t realize how tired I was. I sank eagerly into the worn seat, my spine cradled by the rotting foam. All the places the pack touched my body were raw, especially across my hips. To not wear the pack was to be incomplete.

Coming down the mountain, the truck swerved and slid though a thousand gravel switchbacks. The tires twitched from road to shoulder. Tom’s hands played a game of which-way-will-it-snap with the steering wheel.

Carla rolled over after a rough switchback. Her head smacked the tailgate. She growled and did not stop.

The growling lasted the duration of the drive down the mountain. Her breathing was short and quick. In the mirror, she didn’t seem to be looking at anything.

Tom looked at me blankly, “I think you spooked her pretty good. She’s never been this vocal.”

The growling continued. “You live very far?”

“About twenty minutes once we get to the main road. Nine miles of these switchbacks.”

“You see many hikers this winter?”

“Oh, sure. They come steady year round. But you choose your torture. Bears or snow. It’s a hard choice.”

“I prefer snow.”

“Looks like you got both. Listen up,” he said abruptly. I listened, but he was quiet. A minute passed. “That’s the luckiest thing I ever heard, getting away from that bear.” He shook his head. “But you only have that knife.”

“It works fine.”

“Yeah. But what will you do?”

We stopped at the main road. Tom pressed the clutch to keep the truck from dying. He pulled onto the highway and whistled.

Kill Town, USA

Kill Town, USA